Telemetry endpoints are not business APIs. They don’t process money, don’t return user data, and don’t decide outcomes. That’s exactly why they are dangerous when implemented carelessly.

This story documents a case where malformed input causes a 500 Internal Server Error in a telemetry endpoint used by ChatGPT — something that should not happen in a production-grade system, regardless of the endpoint’s “importance”.

What this check is — and what it is not

This is not fuzzing. It’s not brute force. It’s not “security research”. It is the simplest possible workflow: replaying a real request and changing one field.

The goal is to validate a basic API contract rule: malformed client input must fail with a 4xx response, not crash the server. Telemetry is not exempt from that rule.

What was tested

When a user interacts with a ChatGPT response (for example, pressing the Copy button), the frontend sends a telemetry request to an internal endpoint:

POST https://chatgpt.com/backend-api/conversation/implicit_message_feedback

The payload includes metadata about the interaction, including a message_id.

The expected format of message_id is clearly a UUID, for example:

"message_id": "74fe5c77-4444-4455-85f7-cf58f679b2d0"

(The value above is randomized.)

How it was tested

The workflow was intentionally minimal:

open DevTools, copy the exact cURL generated by ChatGPT, paste into Rentgen, run the request,

then replace message_id with invalid values and observe the responses.

Rentgen did not need any special configuration here. This was a single captured request, replayed as-is.

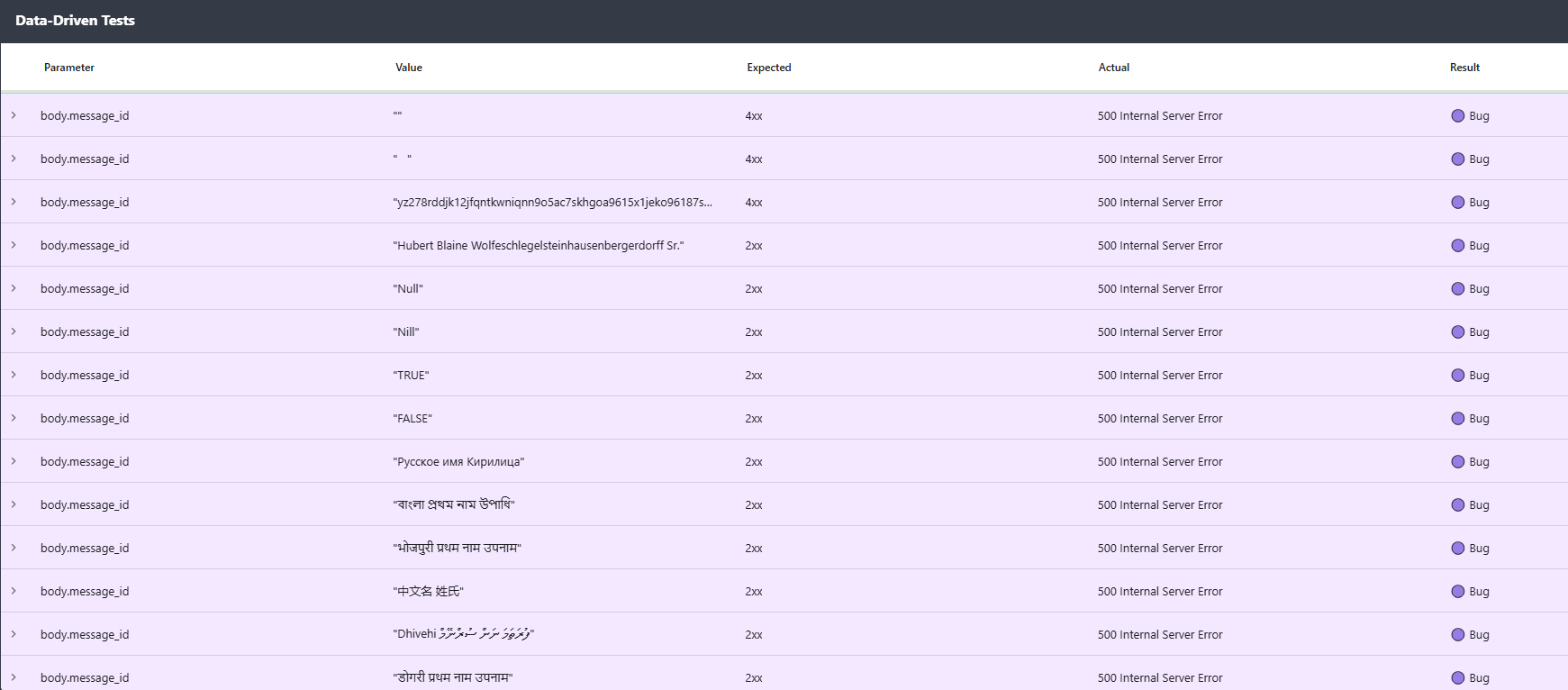

What Rentgen found

When message_id was replaced with arbitrary non-ASCII strings, the endpoint consistently returned:

500 Internal Server Error.

Examples that triggered a 500:

"Tên Việt Nam Họ",

"Lithuanian ąčęėįšųūž",

Danish ÆØÅëáçóáéíâ"

All of these are valid JSON strings. The failure is not “bad JSON”. The failure is server-side handling.

Interestingly, when message_id was replaced with numbers or booleans, the endpoint returned:

422 Unprocessable Entity.

That suggests validation exists — but only at the type level, not at the format level.

Why this is not OK

A 500 error is never an acceptable response to malformed client input.

If a client sends a random string where a UUID is expected, correct responses are 4xx:

400 Bad Request or 422 Unprocessable Entity.

OpenAI already returns 422 in other cases, which is perfectly reasonable and consistent with strict validation.

A 500 response means something else happened: the server accepted the input, attempted to process it, and crashed at runtime.

That is an input validation bug, not a telemetry quirk.

“It’s just telemetry” is a bad excuse

Telemetry endpoints are often called automatically, frequently, and by uncontrolled clients (browsers, extensions, proxies, bots). If an endpoint can be crashed cheaply by malformed input and is not isolated or aggressively rate-limited, it becomes a stability and abuse risk.

At best, it generates log noise and alert fatigue. At worst, it becomes a denial-of-service vector. Telemetry should fail quietly. It should not crash loudly.

What a robust implementation should do

The expected flow is boring and correct: validate schema and UUID format first, fail fast with a 4xx response on invalid input, then parse and process only validated data. If telemetry processing fails internally, it should be handled gracefully without returning 500s.

Rentgen certificate result

When evaluated against Rentgen’s certificate criteria, this endpoint scores 15 / 100 and does not qualify for a certificate badge. The score reflects unsafe assumptions about input format and a runtime crash pattern that production systems should not exhibit.

Final thoughts

This kind of bug is easy to introduce, cheap to fix, and expensive to discover during an incident. The surprising part is not that it exists — it’s how quickly it was found: one copied cURL, pasted into Rentgen, and reproduced in minutes. That is the entire point of Automation Before Automation.