HTTPS doesn’t stop caching. It stops eavesdropping — but caching is your own browser, a mobile WebView, a corporate proxy, or a CDN edge quietly keeping copies of responses because that’s what caches do. And if your API returns anything private (tokens, PII, account data, internal IDs), a cached copy is basically data left behind.

What was tested

Rentgen checks responses from authenticated / private endpoints and verifies that caching is explicitly restricted. The expected baseline for private data is to see headers that clearly tell clients and intermediaries: do not store and do not share across users.

What Rentgen found

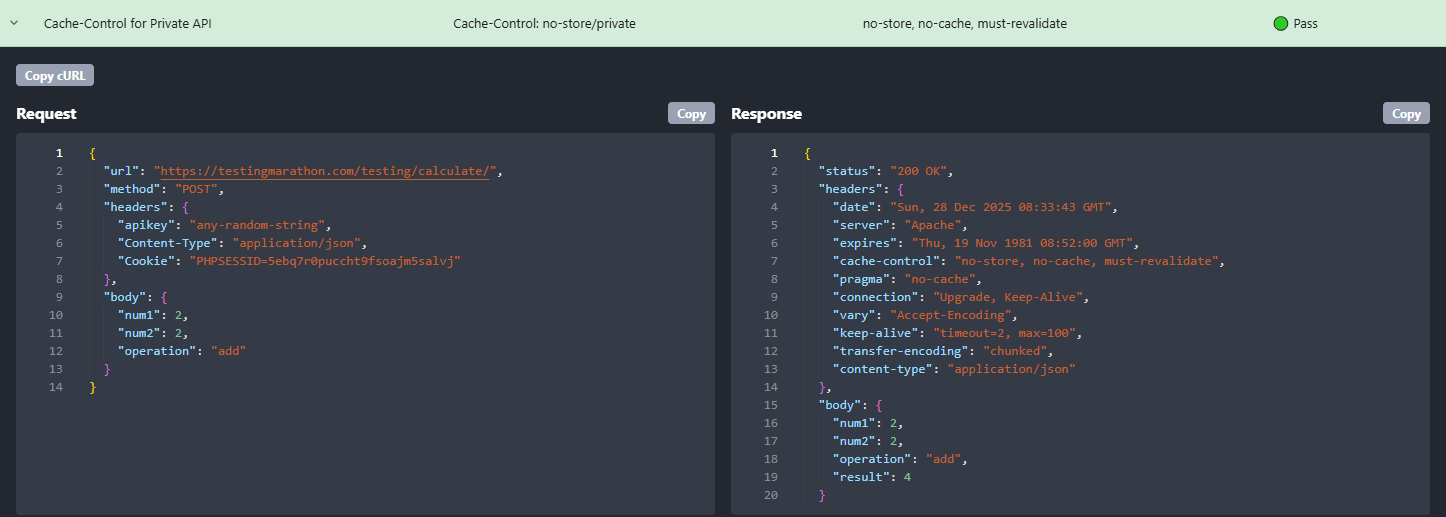

- TEST: Cache-Control for Private API

- Expected:

Cache-Control: no-storeand/orprivate(often withno-cache,must-revalidate) - Example result: 🟢 Pass (

no-store, no-cache, must-revalidate) - If missing: Rentgen marks it as 🔴 Fail — not a warning — because the impact is real and common: private responses become cacheable.

Why it’s a fail (not a warning)

This isn’t “nice-to-have hygiene”. It can become a real data exposure issue without any hacking. When a private response is cacheable, you can end up with sensitive data showing up later through normal behavior: a user logs out and hits Back, a shared machine reopens a page, a proxy serves a cached response, or a mobile app persists a response unintentionally.

What’s the worst that can happen?

Not “someone runs a CVE exploit”. More boring. More painful:

- Account data appears after logout (Back button, refresh, or cached views)

- Tokens / identifiers linger in caches and logs on disk

- PII sits in browser cache and turns into screenshots and incident reports

This is why teams who’ve been burned treat caching headers as baseline security behavior, just like authentication and correct 4xx/5xx handling.

Who should take this seriously?

If your API returns anything user-specific, this matters: banking/fintech, healthcare, gov portals, internal admin tools, B2B dashboards — anything with sessions/cookies/bearer tokens, and anything returning names, emails, IDs, invoices, permissions, or reports. “Internal only” doesn’t save you. Internal leaks are still leaks.

When can you ignore it?

You can often relax strict no-store rules when the response is not sensitive and caching is intentional: public, non-auth endpoints; static reference data; public docs; public OpenAPI specs; version manifests that contain no secrets. But the moment it’s authenticated and user-specific, treat caching like a loaded gun.

Why do many APIs still miss it?

Because it’s not exciting. It’s not visible in UI. Nothing breaks.

People assume “API-only” means “no caching risk”, forget that browsers and proxies still exist,

or rely on reverse proxies and gateways that override headers inconsistently.

Another classic mistake: people think no-cache means “don’t store”.

It doesn’t. It means “must revalidate before reuse”.

How to fix it (the pragmatic default)

For private/authenticated endpoints returning sensitive data, a safe baseline is to explicitly disable caching. Typical configuration ends up with something like:

Cache-Control: no-store, private- often add:

no-cache, must-revalidate - sometimes also:

Pragma: no-cacheandExpires: 0for legacy behavior

The exact combo depends on your stack, but the intent is always the same: don’t leave private data lying around.

Why I put this into Rentgen

Because people don’t forget hard things. They forget simple, boring things — until a security review demonstrates “Back button shows private data after logout”. Rentgen keeps this check enabled by default because it’s fast to detect, easy to fix, and high impact when missed.

Final thoughts

If it passes: great — move on. If it fails: don’t argue with it. Add the header and sleep better. This won’t make you feel like a superhero — but it will stop your API from leaving “ghost data” behind where it doesn’t belong.