CORS is not security in the classic sense. It doesn’t protect your API from attackers. What it does protect is something more fragile: how your API is used by browsers.

That’s why this check is informational. It doesn’t say “good” or “bad”. It answers a simpler question: who is your API meant for?

What was tested

Rentgen inspects CORS headers and determines whether the API is:

- Restricted by origin — only specific origins are allowed

- Open / permissive — requests from any origin are allowed

What Rentgen reports

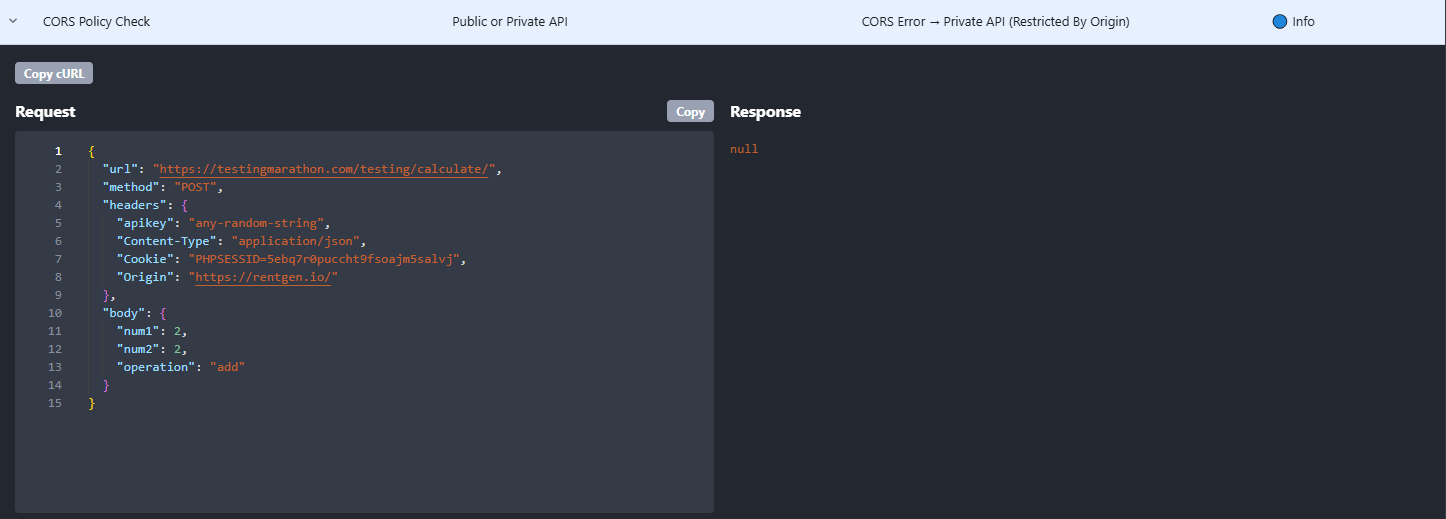

- TEST: CORS Policy Check

- Result: CORS Error → Private API (Restricted By Origin)

- Status: 🔵 Info

Why this is an info-level check

Because CORS configuration is not universally right or wrong. It only makes sense in context.

A private API used by a single web application should almost always be restricted by origin. An external API designed for integrations should usually be accessible from any origin.

The mistake teams make is assuming one default fits all cases. It doesn’t.

Private API vs Public API — the simple rule

If your API is used only by your own web application, and especially if it relies on cookies or browser-managed credentials, then restricting origins is the correct choice.

In that case, CORS acts as a guardrail: it prevents other websites from silently using your users’ sessions to make authenticated requests.

On the other hand, if you are building an API as a product — meant to be called from many different domains and integrations — then strict origin restrictions can become an obstacle.

What OWASP says about it

OWASP treats CORS misconfiguration as a common risk, especially when combined with cookies or implicit authentication.

The key point OWASP makes is simple: CORS should never be overly permissive by accident. Open origins are acceptable only when the authentication model does not rely on browser-managed credentials.

In other words: open CORS is not the problem — open CORS combined with cookies is.

When open CORS can be acceptable

There are valid cases where allowing all origins is fine:

- The API does not use cookies

- Authentication is done via explicit bearer tokens

- Tokens are stored in application code or local storage

- The browser does not automatically attach credentials

In this model, CORS becomes less about protection and more about developer convenience. The browser cannot “leak” credentials it doesn’t automatically send.

Why teams still get this wrong

Because CORS lives in an uncomfortable space between frontend and backend.

Backend teams often assume: “CORS is frontend stuff.” Frontend teams assume: “The backend knows what it’s doing.”

The result is usually a copy-pasted configuration:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *,

added to “make things work” during development

and quietly shipped to production.

Real-world impact

CORS issues rarely show up as dramatic breaches. They show up as:

- unexpected browser errors

- integrations that work from curl but not from browsers

- APIs that cannot be reused outside their original app

- security reviews flagging “overly permissive CORS” late in the process

By the time someone notices, changing CORS often breaks existing clients.

Why Rentgen checks this

Not to judge. Not to fail. But to force the question early: is this API private or public?

Once that question is answered consciously, the correct CORS configuration usually becomes obvious.

Final thoughts

CORS won’t stop attackers. But it will absolutely shape how your API is used, misused, and integrated.

Treat it as an architectural decision, not a checkbox. Rentgen marks this as Info for a reason — because understanding your intent matters more than blindly passing a test.